The endangered Loggerhead Turtle nests on Yaroomba Beach. It is our contention that a light-emitting high-rise resort, proposed by Sekisui House for Yaroomba, will negatively impact on the survival chances of this species.

It is very easy to approach this subject matter from only an emotional point of view, however, in order to counter Sekisui's questionable turtle survivability claims we are not relying on emotion, we are putting forward solid facts based on scientific evidence. Everything written here is referenced and sourced.

There are two species of Marine turtles nesting on Yaroomba Beach and elsewhere . The Loggerhead, which is classified as endangered under the EPBC Act, and the Green which is classified as vulnerable.

Even though current Conditions of approval of the DA suggest that a Turtle Expert must be employed to make sure all works and development protect the Turtles, it is difficult to see how this is possible with the scale of building on the site.

LIGHT POLLUTION

Artificial light poses a threat to marine turtles because it disrupts critical behaviours. Marine turtles use light as an orientation cue. Artificial light can inhibit nesting by females (Salmon 2003) and can disrupt hatchling orientation and sea finding behaviour (Philibosian 1976, Witherington and Bjorndal 1991).

When hatchlings are attracted to light inland they may be exposed to increased mortality from avian and terrestrial predators, trapped in vegetation or killed on roads. If hatchlings do reach the ocean they may have used valuable energy reserves required to reach pelagic feeding areas. Lighting of jetties, vessels or platforms can create pools of light that attract swimming hatchlings and increase their risk of predation (Thums et al. 2016).

Artificial light can therefore cause a gradual decline in the reproductive output of a nesting area, with changes not evident for decades because of the long life cycles involved.

Marine turtles nesting on beaches in Western Australia and south-east Queensland have been identified as being at highest risk from the effects of light pollution from urban and industrial development (Kamrowski et al. 2016).

As hatchlings orient towards the lowest light horizon rather than being directly attracted to bright lights, lights of any wavelength can affect behaviour (Limpus and Kamrowski 2013, Limpus et al. 2015, Robertson et al. 2016) and light glow can disrupt marine turtles when it out-competes natural light sources (Hodge et al. 2007) (Kamrowski et al. 2104, Thums et al. 2014).

Light pollution is managed at the local council level, except in instances where state/territory or Commonwealth environmental approvals require the management of light by a proponent. There are a range of guidelines available to provide advice to proponents, consultants or the general public, but as a general rule turtles require naturally illuminated beaches for successful nesting and sea finding behaviour (Limpus et al. 2015, Robertson et al. 2015).

A growing problem facing sea turtle populations is the increasing demand for urban and industrial development on or adjacent to nesting beaches. This results in a subsequent increase in artificial illumination falling on coastlines, termed ‘light pollution’. Light pollution frequently disrupts both nesting female turtles and the sea-finding ability of emerging hatchlings (Lorne and Salmon 2007; Bourgeois et al. 2009; Berry et al. 2013).

When hatchling sea-finding behaviour is disrupted, the prospect for hatchling survival significantly diminishes (Witherington and Martin 2003).

Following nest emergence, sea turtle hatchlings typically crawl directly towards the shoreline by using environmental cues (Lorne and Salmon 2007).

The principle cue used is visual, based on the direction of the light is coming from and elevation of the beach relative to the horizon (Limpus and Kamrowski 2013). Hatchlings orientate away from dark, high silhouettes and move toward the light horizon line at the lowest angle of elevation (Lohmann and Lohmann 1996; Limpus and Kamrowski 2013)

Night time artificial illumination pollutes nesting beaches and degrades the environmental visual cues commonly used by hatchlings to assist in the navigation from their nest to the sea (Salmon 2003; Tuxbury and Salmon 2005).

Artificial lights have the potential to overwhelm natural light and shape and cues, which results in hatchling disorientation or misorientation (Salmon et al. 1995; Salmon and Witherington 1995). Hatchlings that are disorientated will crawl in no set direction and can circle aimlessly for hours, using up vital energy reserves necessary for a successful off-shore swim (Salmon and Witherington 1995; Pilcher and Enderby 2001; Hamann et al. 2007; Rich and Longcore 2013).

Misoreintated hatchlings will crawl in a set direction, but away from the appropriate direction, typically crawling towards an inland artificial light source (Salmon and Witherington 1995). Both misorientated and disorientated hatchlings can become physiologically stressed by dehydration, and are frequently preyed on by terrestrial predators or killed after sunrise because of exposure to high temperatures (Bustard 1972; Witherington and Bjorndal 1991; Rich and Longcore 2013).

Although wave orientation and the earth’s magnetic field are the principle cues used to orientate the off-shore swim, artificial light can also affect this process, by attracting hatchlings towards the light source, even after the hatchlings have left the shore (Thums et al. 2016). It is estimated that during the 2014-15 nesting season on Heron Island, between 765 and 1752 green turtle hatchlings were likely to have perished because of being misorientated by shore-based light pollution after they had entered the water and commenced their off-shore swim (Truscott, Booth and Limpus 2017).

It is well documented that light pollution disrupts hatchling sea-turtle sea-finding behaviour (Witherington and Bjorndal 1991, Witherington 1992; Salmon and Witherington 1995; Witherington and Martin 2003; Berry et al. 2013; Limpus and Kamrowski 2013; Kamrowski et al. 2014a).

Disruption to sea-finding behaviour can occur up to 500m away from the light-pollution source (Salmon 2003; Tuxbury and Salmon 2005).

It is well documented that night-time artificial illumination present on nesting beaches distracts hatchlings emerging from their nests and discourages nesting females from coming ashore (Witherington 1992; Salmon et al. 1995; Berry et al. 2013 Limpus and Kamrowski 2013). Hatchlings that have entered the sea and begun their off-shore swim can be attracted back to shore by land-based artificial lights (Truscott, Booth and Limpus 2017).

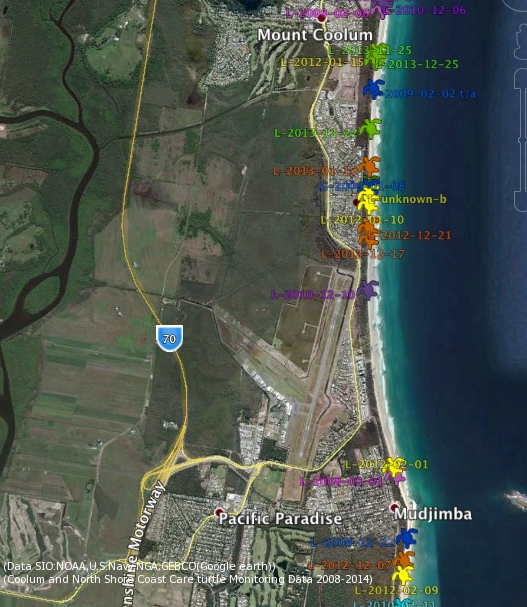

A PICTURE TELLS A THOUSAND TURTLE STORIES

Monitoring Data from the Coolum and North Shore Coast Care Turtle Monitoring Team clearly shows the impact of nocturnal light pollution on prospective (and pre-existing) turtle nesting sites.

The graphic on the left shows coastline turtle nesting sites between Mount Coolum and Mudjimba. Since 2008 the long stretch of beach opposite the high-rise light emitting SurfAir complex has been totally clear of turtle nesting sites. The coastline on either side of the high-rise complex contains many nesting sites.

THE FACTS

Nocturnal light pollution disturbs nesting female turtles. The ability of newly emerged hatchlings to find the sea is disrupted by light pollution from beachside high-rise resorts.

Loggerhead Turtles are already listed as 'Endangered'.

The coastline in front of the light polluting Surf-Air high-rise development has been empty of turtle nesting sites since 2008. Light pollution from the Sekisui high-rise development at Yaroomba will impact on the survival rate of the nesting turtle population on Yaroomba Beach.

LIST OF REFERENCES

Berry, M., Booth, D. T., and Limpus, C. J. (2013). Artificial lighting and disrupted sea-finding behaviour in hatchling loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) on Woongarra coast, south east Queensland, Australia. Australian Journal of Zoology 61

Bourgeois, S., Gilot-Fromont, E., Viallefont, A., Boussamba, F., and Deem, S. L. (2009). Influence of artificial light, logs and erosion on leatherback sea turtle hatchling orientation at Pongara National Park, Gabon. Biological Conservation 142, 85-93.

Bustard, H. R. (1972). ‘Sea Turtles: natural History and Conservation.’ (Collins; Sydney.)

Hamann, M., Jessop, T. S., and Shauble, C. S. (2007). Fuel use and corticosterone dynamics in hatchling green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) during natal dispersal. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 353, 13-21.

Hodge W, Limpus CJ and Smissen P (2007) Hummock Hill Island Nesting Turtle Study December 2006. Conservation Technical and Data Report. Environmental Protection Agency, Queensland.

Kamrowski RL, CJ L, Pendoley K and Hamann M (2014) Influence of industrial light pollution on the sea-finding behaviour of flatback turtle hatchlings. Wildlife Research 41: 421-434.

Kamrowski, R. L., Limpus, C., Jones, R., Anderson, S., and Hamann, M. (2014a). Temporal changes in artificial light exposure of marine turtle nesting areas. Global Change Biology 20, 2437-2499.

Kamrowski RL, Limpus CJ, Moloney J and Hamann M (2012) Coastal light pollution and marine turtles: Assessing the magnitude of the problem. Endangered Species Research 19: 85-98.

Limpus CJ and Kamrowski RL (2013) Ocean-finding in marine turtles: The importance of low horizon elevation as an orientation cue. Behaviour 150: 863-893.

Limpus CJ, Kamrowski RL and Riskas KA (2015) Darkness is the best lighting management option at turtle nesting beaches. In Proceedings of the Second Australian and Second Western Australian Marine Turtle Symposia, Perth 25-27 August 2014, Whiting SD and Tucker A, Eds. Science Division, Department of Parks and Wildlife, Perth, Western Australia. pp 56.

Lohmann, K., and Lohmann, C. (1996). Orientation and open-sea navigation in sea turtles. The Journal of Experimental Biology 199, 73-81.

Lorne, J. K., and Salmon, M. (2007). Effects of exposure to artificial lighting on orientation of hatchling sea turtles on the beach and in the ocean. Endangered Species Research 3, 23-30.

Philibosian R (1976) Disorientation of hawksbill turtle hatchlings, Eretmochelys imbricata, by stadium lights. Copeia 1976: 824.

Pilcher, N. J., and Enderby, S. (2001). Effects of prelonged retention in hatcheries on green turtle )Chelonia mydas) hatchling swimming speed and survival. Journal of Herpetology 35, 633-638

Rich, C., and Longcore, T. (2013). ‘Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting.’ (Island Press: New York.)

Robertson K, Booth DT and Limpus CJ (2016) An assessment of ‘turtle-friendly’ lights on the sea-finding behaviour of loggerhead turtle hatchlings (Caretta caretta). Wildlife Research 43: 27-37.

Salmon M (2003) Artificial night lighting and sea turtles. Biologist 50: 163-168.

Salmon, M., and Witherington, B. E. (1995). Artificial lighting and seafinding by loggerhead hatchlings: evidence for lunar modulation. Copeia 1995, 931-938.

Salmon, M., Tolbert, M. G., Painter, D. P., Goff, M., and Reiners, R. (1995). Behaviour of loggerhead sea turtles on an urban beach. II. Hatchling orientation. Journal of Herpetology 29, 568-576.

Shimada T, Limpus CJ, Jones R, Hazel J, Groom R and Hamann M (2016) Sea turtles return home after intentional displacement from coastal foraging areas. Marine Biology 163

Thums M, Whiting SD, Reisser JW, Pendoley KL, Pattiaratchi CB, Proietti M, Hetzel Y, Fisher R and Meekan M (2016) Artificial light on water attracts turtle hatchlings during their near shore transit. Royal Society Open Science 3: 160142.

Truscott, Z., Booth, D. T., Limpus, C. J. (2017). The effect of on-shore light pollution on sea-turtle hatchlings commencing their off-shore swim. CSIRO Publishing, Wildlife Research 44, 127-134.

Tuxbury, S. M., and Salmon, M. (2005). Competitive intercations between artificial lighting and natural cues during seafinding by hatchling marine turtles. Biological Conservation 121, 311-316

Witherington, B. E. (1992). Behavioural responses of nesting sea turtles to artificial lighting. Herpetologica 48, 31-39.

Witherington BE and Bjorndal KA (1991) Influences of artificial lighting on the seaward orientation of hatchling loggerhead turtles Caretta caretta. Biological Conservation 55: 139-149.

Witherington, B. E., and Martin, E. R. (2003). Understanding, accessing, and resolving light-pollution problems on sea turtle nesting beaches. 3rd edn. Florida Marine Reseacrh Institute technical report 73. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Jacksonville, FL.

The Save Yaroomba Group (as a sub committee of Friends of Yaroomba Inc) is dedicated to the preservation of social amenity in the Yaroomba Village area. We are not opposed to appropriate development or economic growth across the Sunshine Coast region or the Yaroomba Beach precinct. We are opposed to the Sekisui Yaroomba Beach development because it does not conform to the reasonable restraints contained in the Sunshine Coast Planning Scheme 2014. The Sekisui DA will greatly affect the social environment for all residents in the Yaroomba Beach Community, and our aim is to ensure that the Sekisui Yaroomba proposal fully adheres to the height and density requirements stipulated for the Yaroomba Beach district in the Sunshine Coast Planning Scheme 2014. We welcome appropriate development to Yaroomba Beach, but we will strenuously oppose the current form of the Sekisui Yaroomba Beach proposal. If you would like to support our cause to save the Yaroomba Beach Community from this inappropriate Sekisui Yaroomba development, you are welcome to either donate via the facility on this website, or join our email list to receive updates.